How well can the tracker data that’s available to me upon waking foretell my health status, as a person with ME/CFS (PWME), for the rest of the day? Over the past few years, I have applied a plethora of machine learning techniques to answer this question. The goal was to create an app to automatically predict PWME’s daily health each morning.

The result is disappointing: the best method will accurately predict whether my daily health will be ‘bad’ or ‘not bad’ only 57 percent of the time. Flipping a coin would result in 50 percent accuracy, so this is an improvement of only 7 percent.

I still believe that resting heart rate (RHR) and heart rate variability (HRV) generally change along with my health status, so what went wrong? My observation is that many other factors also influence these measurements, masking the relationship that I’m trying to model. The good-ish news is that a person likely can do a better job of taking these contingencies into account, making this a case when human learning probably outperforms machine learning.

The following post will discuss my work in general terms. The first part is a discussion geared toward other PWME, and the second goes over the many data science approaches I tested. For further details: some of the code and results are on Github, and I invite the curious to contact me directly.

Why HRV and RHR don’t predict well

Using my Garmin tracker, I can see clearly that my heart rate and HRV patterns change markedly when I’m in post-exertional malaise (PEM) or when I over-exert myself physically or emotionally. And, indeed, I have observed that RHR and HRV are ‘worse’ – higher and lower, respectively – overnight when I am in PEM. Thus, it seems reasonable that they would be powerful predictors of daily health. But, statistically, they aren’t. So why not?

The reason, I suspect, is that many other changes can also alter RHR and HRV, for example:

- combatting an infection, even if I’m not symptomatic

- eating a heavy meal, e.g. pizza, the previous night

- nervousness or excitement about some impending event

- seasonal allergies (in my case, technically not allergies but ‘sensitivities’)

- taking acetaminophen or cannabis (among other pain relievers) to reduce PEM symptoms.

- That is, the pills I take because of PEM reduce these signs of PEM.

The first four of these scenarios look similar to PEM in my dataset, even though my daily health might not be bad. In short, a high RHR and low HRV are symptoms of PEM but aren’t specific to it. Since it’s unrealistic to expect PWME to code all possible confounding causes of ominous readings, creating a general method of prediction seems doomed to failure.

However, if you know that your RHR and overnight HRV look bad because of PEM – or that there isn’t another good explanation for their high or low levels – then you might do a better job than a statistical technique in predicting your health that day.

Bad omen: Low correlations

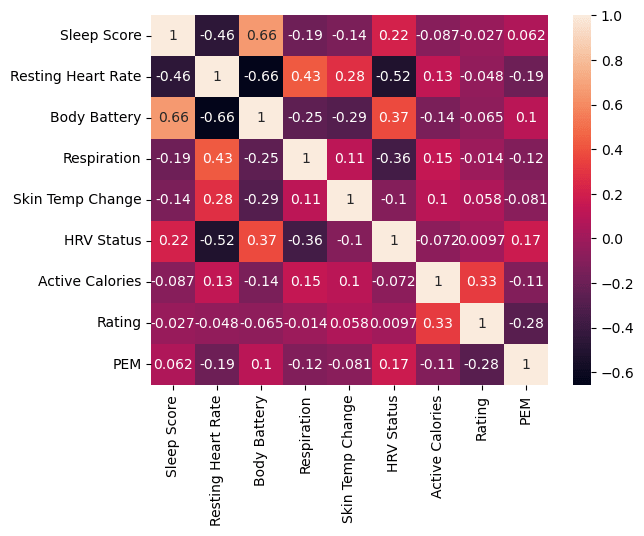

The rest of this post outlines my attempts to create a useful statistical predictor. The low probability of success was evident from the start, given the low correlations among the various predictors and outcomes I tested:

Nevertheless, I persisted.

An exhaustive search

I began this project several years ago, and my health, treatments, Garmin tracker models, and analytical expertise have all changed since I began. So, in fact, has the goal of this research. In order, I tried to predict:

- The day between overexertion and before full-on PEM symptoms

- Days of PEM

- Garmin’s estimate of my active calories

- My rating of daily health on a scale of 1 (horrible) to 5 (great)

- Bad days included PEM and non-PEM days. Personal experience and my reading of the research lead me to understand PEM as a qualitatively different state rather than simply any worsening of symptoms.

- A binary version of the daily rating, contrasting ‘bad’ (1-2) and ‘not bad’ (3-5)

- The most successful model used this target.

First attempt

The first round of research used data from a disease-tracking spreadsheet that I developed. The data covered a few years, including times when I was housebound and times when I was fairly active. I recorded PEM directly as a binary variable, but I also performed analyses on a composite score of symptoms in an attempt to capture differing severity.

After extensive data preparation:

- Imputation

- Moving averages of baseline values

- Ignoring days with PEM or days adjacent to PEM days

- Percentage change from recent baseline

- Difference from recent baseline

- ROSE data-balancing

I created the following types of models, testing different hyperparameters and sets of predictors using cross-validation:

- Logistic regression (least-bad model)

- SVM

- Random forest

- K nearest neighbors

- XGBoost with Bayesian parameter estimation

- K-means

- Hierarchical clustering

Initially, I analyzed the full dataset, without testing accuracy on a test set. Unfortunately, none of the approaches showed enough promise to move past exploration. Thus, the accuracy on unseen data was likely to be significantly lower than the unimpressive results I obtained.

Second attempt

Earlier this year I tried again using different analytical tools. I built models using the dataset described above and a more recent one that included new outcomes in addition to PEM – daily health rating and estimated active calories. This dataset covered 9–11 months, depending on when I performed the work.

Once again, after extensive data prep similar to that described above, I tested a variety of models. However, this time each model’s accuracy was measured on a test set. And the list of predictors was longer, thanks to a new tracker. Here are the methods I used:

- Deep neural networks (using Keras in Python)

- Outcomes

- Binary classification of daily ratings

- Collapsing five levels into ‘bad’ and ‘not bad’

- This was the most successful, with 57 percent accuracy – or a 7 percent improvement over random guessing.

- Ordinal classification of daily ratings (1–5)

- Regression of daily ratings

- PEM classification

- Active calories regression

- Binary classification of daily ratings

- Outcomes

- Gradient boosted trees (using scikit-learn and LGBMOrdinal)

- Predicting the same outcomes as above, with similar results in each case

- Time-series forecasting (using NeuralProphet and pmdarima)

- Outcomes: PEM or daily rating (5-point scale and binary)

- Data: created models with each dataset

- The predictors named above were included as exogenous regressors

- Result: After much testing, I found that the best models performed the same as simply autoregressing on the previous day. That is, they added no value beyond predicting that today’s health will be like yesterday’s.

- Time-series segmentation (using ClaSPy)

- To differentiate normal periods from PEM

- Data: created models with each dataset, but did not create a test set

- Result: It predicts about half as many changepoints as I recorded, and it actually matches less than 20%. And this is the best-case scenario, ‘overfitting’ to the full dataset.

- Nonetheless, testing hyperparameters did clearly identify the combination of RHR and HRV Status as the best set of bad predictors.

Conclusion: I give up

In sum, this wide-ranging exploration – which is described only partially here – has convinced me that my data, and possibly tracker data in general, cannot be used to create a statistical predictor of daily health for PWME. While the best model creates a 7 percent improvement over random guessing, I probably can do better by contextually interpreting the tracker’s output and my experience of symptoms.